Wei Chen received the University of Tartu Asia Centre scholarship for his MA thesis on the omen system

We are pleased to announce that the University of Tartu Asia Centre scholarship in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities was awarded to Wei Chen for his MA thesis. Read about why he chose the topic and his own personal connection to it.

What was your main trigger while choosing this topic for your thesis on the omen system of Eastern Minyag in the People's Republic of China (PRC)?

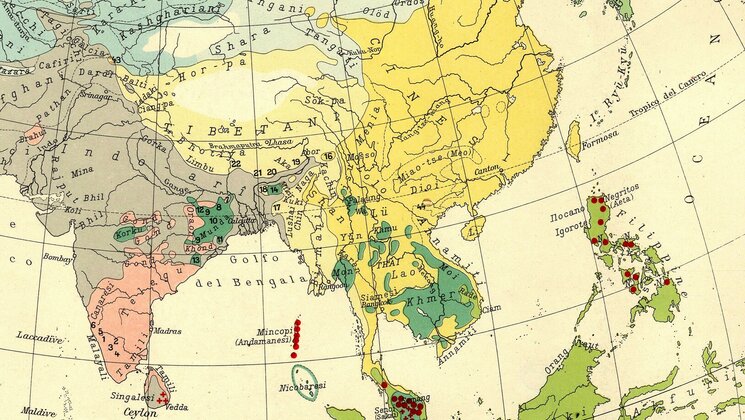

I am from one of the Eastern Minyag mountain villages, which still considerably preserves Minyag traditions. When I was a small herdsman in the wild with old herders, they always heard how to recognize and avoid omens from them. This background gave me the basic idea of the Minyag's omen and triggered my curiosity about the omen. Coming to Estonia and studying folkloristics is a beautiful opportunity to explore folklore. During my studies, many cases inspired me to keep an eye on the Minyag omens. After I had read the previous research about omens, I found that they are always stigmatized as superstitions and irrationality. This caused me to do something to eliminate the bias of omens. Eastern Minyag is a very small sub-group of Tibetans in China, around 4,500 people. Local Minyag people do not know their history and origin as a tiny group, but they care more about the future. The Minyag omen system is a tool to predict the future, but it also hides the Minyag history in the omen system. The studies of omens can be the middle point to connect history and the future, Minyag and the world. Therefore, several factors cause me to focus on the Minyag omen system.

What challenges did you face during your research, and how did you overcome them?

During my research, the most challenging part was fieldwork. Although I am a community member, the fieldwork is not easy for me, especially the informed consent. First, Minyag communities are small, and most villagers are relatives, so people may answer interviews and give informed consent out of deference instead of voluntarily sharing their stories. It is hard to get their sincere opinions. Second, the direct experience of an omen is often accompanied by personal trauma; people are unwilling to talk about their omens, but other people’s stories can be gossiped about. To address these issues, I used anonymity to avoid hurting the people mentioned in the conversation and used the interview skills I learned from the BA social work training. However, the interview skills are not enough; a trusting relationship must be built. Due to my experience of having already conducted fieldwork for five years in the Minyag communities, we built a good level of trust that allowed them to tell me their sincere opinions.

Were there any surprising or unexpected discoveries in your research?

After the data collection, three main points shocked me, which I had never noticed. First, unlike the omens in other cultures, which consist of positive and negative omens, Minyag omens are all negative. However, as Minyag people perceive the omens, they can change their misfortune through specific actions. In some way, positivity is hidden behind the negativity of omen phenomena as they are vital signs for preventing future suffering. By recognizing and addressing these omens, people can mitigate potential difficulties. Second, the Minyag omen is generally connected to the zodiac, meaning that only signs cannot be considered omen. Only the day’s zodiac, personal zodiac, and ominous signs co-occur; then, it can be called an omen. Interestingly, this practice of linking the zodiac with omens is not unique to the Minyag. In the ancient textual research of Mesopotamia(especially in the Neo-Babylonian period), there are also many similar omens. However, the omens of Mesopotamia exist in cold texts, while the omen system of the Eastern Minyag is still vibrant. Third is the transferability of Minyag omen. In Minyag, some people try to transfer the suffering of omens to other Minyags or outside of the community. In traditional ways, omens can be moved by rituals, such as calling others to watch an omen or letting others respond to the calling. Today, Minyag has more choices to transfer by modern ways, like TV, internet, books, phone, or TikTok. Even during the pandemic, there was a voice in the village, Minyag people transferred too many omens to the outside of the community, causing this world disaster.

Estonian folklore is allegedly rather rich of using different omens, especially in older generations. Younger ones do not take it very seriously; however, the majority of the youth is still aware of it. Considering the current situation in Eastern Minyag region today then how about there, is the younger generation still using the omen system? And what do you think, how do they take it?

Today, urbanization is happening in the Minyag region, and many Minyag mountain villages have disappeared; during this time, the knowledge of omen is also interesting. The previous animistic worldview was not wholly destroyed before a new scientific materialistic worldview was built up. In Minyag, many young generations still believe in and practice the Minyag omen system, but they always try to give the omens reasonable explanations from a scientific view. They gave up some traditional omens; for example, young people no longer see solar eclipses as omens. On the one hand, we can see the youth did not get enough knowledge of the omen system as they lost the omen training environment in the community. Some specific omens' knowledge is only transmitted in certain groups, such as herdsmen’s omens are not known by others. As Minyag's young generations mainly live outside of the community because of study and jobs, what omens they know are close to modern life, like car crash birds instead of pig-eating piglets. However, I believe these omens practiced among young people should be called pragmatic omens. Traditional omens are based on the Minyag traditional modes of life and production. The impact of modernization and urbanization entailed transforming Minyag's social life. We can now see that pragmatism is starting to address the gap between old and required omens. In the past, this dialogue happened between the static manuscripts and the living omens. There are 12 omens in the manuscripts, but Minyag people only picked the useful ones, thus disregarding abstract and rare omens. Today, youth only pick useful omens and abandon rural characteristics of omens far away from their city lives.

What are the three most important findings from your thesis that should be more widely known here for Estonians?

First, omens are a sort of vernacular knowledge to understand individual life and collective surroundings. It should not be seen as superstition and ignorance. Second, the omens mirror local social, cultural, and political history. Omens play an important role in preserving and processing the memory for the future generations. Some information of political stress, historical survival issues, and collective dissatisfaction are hidden in the omens. Third, omens are based on the individual and collective experiences of life. The omens similarly act as a filter between individual and collective memories, enabling their mutual transformation.

What advice would you give to other students or researchers interested in this field?

Omen studies are an interesting topic for exploring the ancient and contemporary lifestyle. First, always consider the ethical implications of research. Respect the beliefs and traditions of the communities studied, and ensure that work does not exploit or misrepresent them. Second, the over-through of the previous studies of omen classification will be a good method to understand the history of omen research. That can cause students to carefully use the terminology, which is important to describe the understanding of this genre. Third, Comparative analysis should be widely applied to discover the differences and similarities of omens in different cultures. Develop a deep understanding of the omen culture within specific ethnic groups. This requires sensitivity to their life, culture, history, and real experiences. Immersing yourself in the community and engaging with local practices and beliefs can provide invaluable insights.

Thank you!

Interview with the author after his graduation ceremony in 2024

Questions: Evelyn Pihla